T: It recently struck me that you're often described as a performance poet, as if this is an entirely different kind of poet—is it?

AW: No. Of course not. I am a poet, bard, scop, minnesinger, trobairitz who is driven by sound and the possibilities for vocal expression, the mouthing of text as well as intentionality or dance on the page. Orality goes with the description of poet in the primary sense when poetry was composed by people who didn't read or write. It was generated for ritual purposes and for cosmological and mythical and chronological purposes: telling the story of a particular tribe, a particular battle and defeat or victory that sort of thing. Epic and ballad are the narrative forms. Then there's incantation, love song, lament, dirge, curse, spells, mantra, songs for fertility, etcetera. As well as sonnet, sestina, pantoum, ode which also have oral roots. I've worked in all these forms (in some cases composing on the spot) and extended them and come to my own shapes. I also grew up on classical music, folk music, and jazz. Ideas arrive as oral ideas that evolve into modal structures-clear musical patterns. Vocal range interests me, Sprechstimme interests me, timing interests me, collaboration with instruments and other voices interests me. I'm drawn to the magical efficacies of language as a political act. And to musics, rituals and poetries out of India, Tibet, Indonesia, Thailand. When Andrew Schelling and I worked with the Theri and Theragatha poems of the Pali canon (of India) we struggled to revive the oral moment of these renunciant monks and nuns. These poems were originally sung in a tradition passed down for centuries before written down in 80 B.C.E. Much of my praxis is a gaze toward the East, if you will, mingled with all these other tendencies.

I am a thing to do. A window

broken by my own head flying

through. I was pushed or I wasn’t.

You should walk away, but you

can’t. You can’t trust me. Don’t.

Love me. Call me sweetheart

like you mean it. Slide the black

leather from the loop. I’m on

my knees because I’ve fallen

like a dead man in a grave

for you. This is my face darkening

where the glass claimed my cheek,

me smashed into it, me taking it

like a pro. This is my hair, unbrushed

and Dear-God all over. I don’t love

myself and I never will, thighs, clapping,

making room inside

another room. Unbuckle

this breath for me, would you?

I have a heart amongst other things

nobody seems to know how to pull

the beat from. Give me your hand.

I’ll fold it into a hammer. In my ribs,

send it forth. Rattle me loose. It’s been

so long. Let whatever moves, move.

hank you, Derrick Franklin (the other fine man pictured above), for being the love of my life, for dealing with me and without me in the midst of my end of the semester grading and recommendation writing and refusal to sleep or eat because I think I've figured the right word in the last line of some old poem, for being my long distance love who makes both coasts my coast, for letting me flirt with the anonymous and the ridiculous knowing that, in truth, I'm coming home to put my whole check and whatever else you require in the palm of your perfect hand. Thanks for letting me chase whatever it is I think I'll catch when I'm foolish enough to agree to blog for a week at the busiest time of year.

This final post is written in gratitude for the lives and legacies of Rudolph Byrd, the man I credit with teaching me how to read, and to Essex Hemphill, whose poems Dr. Byrd used as the primer for my lessons. I live with their spirits in my ear: no wonder I get where to go!

And finally, thank you Darrel Alejandro Holnes, Saeed Jones, Rickey Laurentiis, Phillip B. Williams, and L. Lamar Wilson for sending me poems and pictures with which to end this week and to share with lovers of poetry who are about to read what the critics call brilliance. Nobody teaches me to be free like the five of you do, THE PHANTASTIQUE 5.

Since I've been asking questions all week, one last interview before all of you enjoy these short lyric poems:

Q: Why spell fantastic like that? Why five instead of four?

A: Hmm...queer, isn't it?

from The Wapshot Chronicle

Chapter One

St. Botolphs was an old place, an old river town. It had been an inland port in the great days of the Massachusetts sailing fleets and now it was left with a factory that manufactured table silver and a few other small industries. The natives did not consider that it had diminished much in size or importance, but the long roster of the Civil War dead, bolted to the cannon on the green, was a reminder of how populous the village had been in the 1860s. St. Botolphs would never muster as many soldiers again. The green was shaded by a few great elms and loosely enclosed by a square of store fronts. The Cartwright Block, which made the western wall of the square, had along the front of its second story a row of lancet windows, as delicate and reproachful as the windows of a church. Behind these windows were the offices of the Eastern Star, Dr. Bulstrode the dentist, the telephone company and the insurance agent. The smells of these offices -- the smell of dental preparations, floor oil, spittoons and coal gas -- mingled in the downstairs hallway like an aroma of the past. In a drilling autumn rain, in a world of much change, the green at St. Botolphs conveyed an impression of unusual permanence. On Independence Day in the morning, when the parade had begun to form, the place looked prosperous and festive.

The two Wapshot boys -- Moses and Coverly -- sat on a lawn on Water Street watching the floats arrive. The parade mixed spiritual and commercial themes freely and near the Spirit of '76 was an old delivery wagon with a sign saying: GET YOUR FRESH FISH FROM MR. HIRAM. The wheels of the wagon, the wheels of every vehicle in the parade were decorated with red, white and blue crepe paper and there was bunting everywhere. The front of the Cartwright Block was festooned with bunting. It hung in folds over the front of the bank and floated from all the trucks and wagons.

from The Death of Justina

"So help me God, it gets more and more preposterous, it corresponds less and less to what I remember and what I expect, as if the force of life were centrifugal and threw one further and further away from one's purest memories and ambitions; and I can barely recall the old house where I was raised, where in midwinter Parma violets bloomed in a cold frame near the kitchen door and down the long corridor, past the seven views of Rome—up two steps and down three—one entered the library, where all the books were in order, the lamps were bright, where there was a fire and a dozen bottles of good bourbon, locked in a cabinet with a veneer like tortoise shell whose silver key my father wore on his watch chain. Just let me give you one example and if you disbelieve me look honestly into your own past and see if you can't find a comparable experience. On Saturday the doctor told me to stop smoking and drinking and I did. I won't go into the commonplace symptoms of withdrawal, but I would like to point out that, standing at my window in the evening, watching the brilliant afterlight and the spread of darkness, I felt, through the lack of these humble stimulants, the force of some primitive memory in which the coming of night with its stars and its moon was apocalyptic..."

I was Mary once.

Somebody big as a beginning

Gave me trouble

I was too young to carry, so I ran

Off with a man who claimed not

To care. Each year,

Come trouble’s birthday,

I think of every gift people get

They don’t use. Oh, and I

Pray. Lord, let even me

And what the saints say is sin within

My blood, which certainly shall see

Death—see to it I mean—

Let that sting

Last and be transfigured.

Credit...

You will notice, however, that some ambiguities are never resolved (“I open Nabokov and am charmed by this spectrum of ambiguities, this marvellous atmosphere of untruth,” Cheever says in his journals)—ambiguities in the matter of sexuality, ambiguities elsewhere. Always another rock with its subterranean communities to overturn and consider. Always the lie that tells a deeper truth. Always a cache so secreted away as to be invisible. The writer under forty who thinks he knows himself is arrogant indeed. It’s in this climate of individuation that we find the opportunity for the psychic density of indirection, in which our foibles, seeded in the mulch of our youth, begin to express themselves in correlatives, as we are driven to get them down, until we have said what we’re here to say and are left instead with quiet and the stir of time past: “Now I’m undressing to go to bed, and my fatigue is so overwhelming that I am undressing with the haste of a lover.”

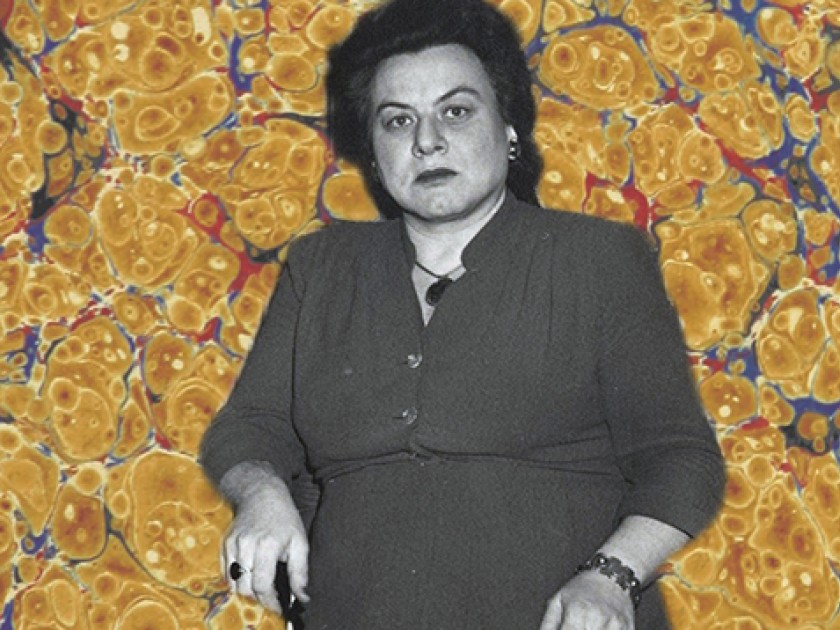

Muriel Rukeyser's Cohort

St. Roach

from Utopia Avenue

1

Abandon Hope

Dean hurries past the phoenix theatre, dodges a blind man in dark glasses, steps onto Charing Cross Road to overtake a slow-moving woman and pram, leaps a grimy puddle, and swerves into Denmark Street where he skids on a sheet of black ice. His feet fly up. He's in the air long enough to see the gutter and sky swap places and to think, This'll bloody hurt, before the pavement slams his ribs, kneecap, and ankle. It bloody hurts. Nobody stops to help him up. Bloody London. A bewhiskered stockbroker type in a bowler hat smirks at the long-haired lout's misfortune and is gone. Dean gets to his feet, gingerly, ignoring the throbs of pain, praying that nothing's broken. Mr. Craxi doesn't do sick pay. His wrists and hands are working, at least. The money. He checks that his bankbook with its precious cargo of ten five-pound notes is safe in his coat pocket. All's well. He hobbles along. He recognizes Rick "One Take" Wakeman in the window of the Gioconda café across the street. Dean wishes he could join Rick for a cuppa, a smoke, and a chat about session work, but Friday morning is rent-paying morning, and Mrs. Nevitt is waiting in her parlor like a giant spider. Dean's cutting it fine this week, even by his standards. Ray's bank order only arrived yesterday, and the queue to cash it just now took forty minutes, so he pushes on, past Lynch & Lupton's Music Publishers, where Mr. Lynch told Dean all his songs were shit, except the few that were drivel. Past Alf Cummings Music Management, where Alf Cummings put his podgy hand on Dean's inner thigh and murmured, "We both know what I can do for you, you beautiful bastard; the question is, What will you do for me?," and past Fungus Hut Studios, where Dean was due to record a demo with Battleship Potemkin before the band booted him out.

The first thing Schatzberg had to do to make this book as heart-rending and poignant as it is was to amass throw-away photos of his friends, the boys in the title, in the seventies. Mere snapshots. There was, it should be clear, nothing innately memorable about these historical photos as photos at the moment they were taken. They are photos of a group of friends of just the sort you might have taken yourself. They were taken as barely collectible documentations of a time, mementoes thereof. What I love about the early photos of The Boys, as Schatzberg’s crew call themselves, is exactly how unpretentious and routine they are. Of course, according to my wife’s advice about putting the photos in a drawer, these photos come radically alive, now, not only because of how much photo vocabulary has changed, but also because of how far away the 1970s seem to us.

And yet Schatzberg’s book lifts off not in the act of curation, however great the meaningful preservation is, but in the portraits of The Boys (aestheticized, in large-format images) now. Knowing the middle aged body of the white man pretty well, I know not only how hard it was to try to get these bodies to look anything but harrowing, dissolute, poignant, human, but also how brave it was of these men to take their shirts off. If American culture is youth-oriented, and about glamor, and sexuality, and if the large-format image, with its chewy detail and richness, is more frequently a thing featuring beautiful people and expensive clothes, then Schatzberg’s loving portrayal here of The Boys now, is both risky and liable to be, for many audiences, at the limit of what is pictographically permitted. Photos designed for the male gaze can be more extreme than this (the patriarchy makes it so), photos for the purposes of social change can be more extreme than this (the tradition of the documentary art makes it so), but photos of creaky, decaying, older white men struggling for dignity are perhaps the hardest photos to look at now. There is no audience, in the strictest sense, for these images, if audience is determined by fashion or by the merchandising demographics of the present.

Richard Avedon. October 10, 1995

“The brain may take advice, but not the heart, and love, having no geography, knows no boundaries: weight and sink it deep, no matter, it will rise and find the surface: and why not? any love is natural and beautiful that lies within a person's nature; only hypocrites would hold a man responsible for what he loves, emotional illiterates and those of righteous envy, who, in their agitated concern, mistake so frequently the arrow pointing to heaven for the one that leads to hell. ”

― Truman Capote, Other Voices, Other Rooms

When Barcelona fell, the darkened glass

turned in the world and immense ruinous gaze,

mirror of prophecy in a series of mirrors.

I meet it in all the faces that I see.

Decisions of history the radios reverse;

Storm over continents, black rays around the chief,

Finished in lightning, the little chaos raves.

I meet it in all the faces that I see.

Inverted year with one prophetic day,

high wind, forgetful cities, and the war,

the terrible time when everyone writes “hope.”

I meet it in all the faces that I see.

When Barcelona fell, the cry on the roads

assembled horizons, and the circle of eyes

looked with a lifetime look upon that image,

defeat among us, and war, and prophecy,

I meet it in all the faces that I see.

When Barcelona fell, the darkened glass

turned in the world and immense ruinous gaze,

mirror of prophecy in a series of mirrors.

I meet it in all the faces that I see.

Decisions of history the radios reverse;

Storm over continents, black rays around the chief,

Finished in lightning, the little chaos raves.

I meet it in all the faces that I see.

Inverted year with one prophetic day,

high wind, forgetful cities, and the war,

the terrible time when everyone writes “hope.”

I meet it in all the faces that I see.

When Barcelona fell, the cry on the roads

assembled horizons, and the circle of eyes

looked with a lifetime look upon that image,

defeat among us, and war, and prophecy,

I meet it in all the faces that I see.

Toomer

(Jean Toomer)

I did not wish to "rise above"

or "move beyond" my race. I wished

to contemplate who I was beyond

my body, this container of flesh.

I made up a language in which to exist.

I wondered what God breathed into me.

I wondered who I was beyond

this complicated, milk-skinned, genital-ed body.

I exercised it, watched it change and grow.

I spun like a dervish to see what would happen. Oh,

to be a Negro is-is?-

to be a Negro, is. To be.

Early Cinema

from What the Women Said

"I am not thinking of exceptional minds, like Cleopatra or Mrs. Carlyle or Jane Austen or Virginia Woolf; I am thinking of the 'ordinary' woman, undistinguished, often unintellectual and introspective. The minds of most women differ from the mind of most men in a way which I feel very distinctly, but which becomes rather indistinct as I try to describe it. Their minds seem to me to be gentler, more sensitive, more civilized. Even in many stupid, vain, tiresome women this quality is often preserved below the exasperating surface.” (Bogan, 1962)

Juan’s Song

When beauty breaks and falls asunder

I feel no grief for it, but wonder.

When love, like a frail shell, lies broken,

I keep no chip of it for token.

I never had a man for friend

Who did not know that love must end.

I never had a girl for lover

Who could discern when love was over.

What the wise doubt, the fool believes--

Who is it, then, that love deceives?

Santa Fe Trail I go separately The sweet knees of oxen have pressed a path for me ghosts with ingots have burned their bare hands it is th...