Die ungebornen Enkel.

is translated as:

The grandchildren — unborn. (148)

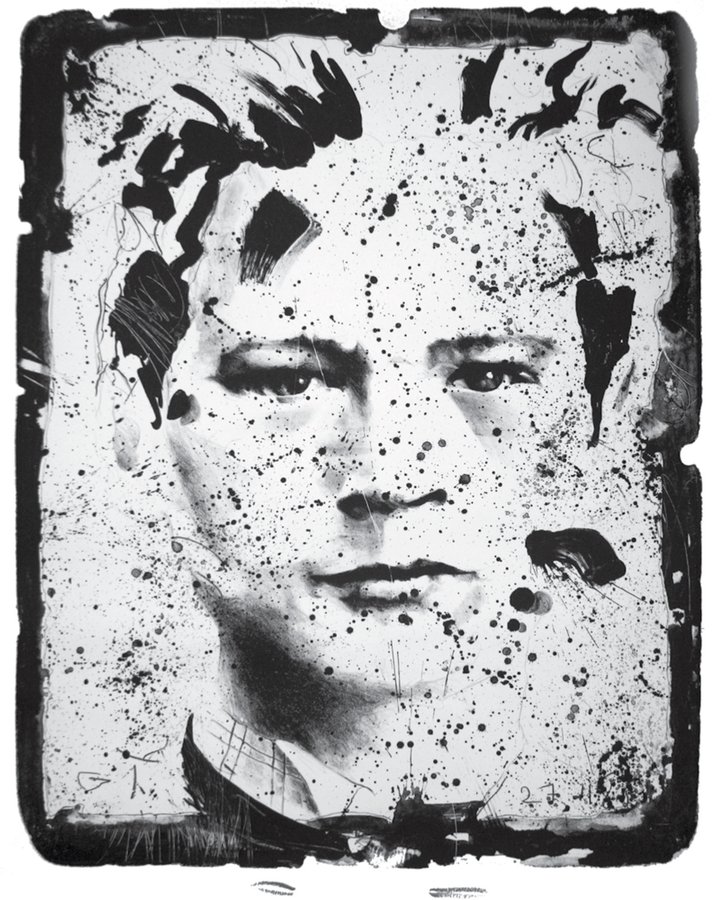

Here, the words match up quite neatly, but it’s Hawkey's differences — from/of/with the Austrian poet — that drive this book. And it's those same differences that put Ventrakl in conversation with all of Trakl's former English translators, who make an interesting bunch. That lineup includes (among others): Michael Hamburger, the great Celan translator immortalized in Sebald's Rings of Saturn; James Wright and Robert Bly, the dynamic duo of the Midwestern deep image; Robert Grenier, the father/uncle of the Language School poets beloved for his minimalist epic A Day at the Beach — all of whom appear in the 1983 volume Georg Trakl: A Profile, edited by Frank Graziano.[1A Profile begins with a question by Rainer Maria Rilke, writing on Georg Trakl: "What could he have been?" (Trakl, 7) — which is apt. What kind of figure could attract and marry the avant-garde tendencies of Grenier with the rural/lyric placidity of James Wright? Hawkey attempts to answer this question by marrying those two aesthetics himself. Poems like “Grodek” are paired with more bizarre translations, such as “Rosencrantz: A Western” or “You Bend My Megahertz,” whose titles alone address the range of permissible interpretation.

The nonstandard translation has its own traditions as Hawkey, in his introduction, points to the work of Jack Spicer, Louis Zukofsky, Anne Carson, and David Cameron, whose Flowers of Badstands out as a particularly dedicated "bad translation" (Cameron's own phrase).[2] Cameron, for example, takes Baudelaire's poems and puts them through chance operations to create works that are the spawn of the great French poet, if translucently so. Hawkey puts Trakl through similar filters, though his methods don't reveal themselves immediately. The resulting language is more Hawkey’s than anyone else's.

In Ventrakl, he echoes Rilke's question:

The question of what?

Of who is speaking.

Who is writing then?

Who is.

Who is. (37)

Who is writing is the translator.