Poetics

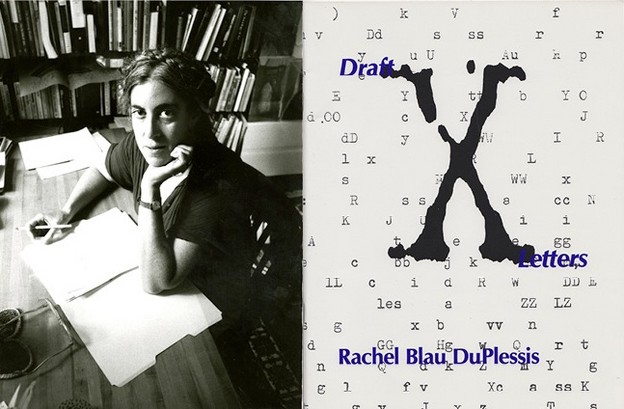

So what about my own praxis? Drafts is a long poem, in autonomous canto like sections, with a projected total of 114 separate but related works; it was begun in 1986. Now it is 2010, and I have eight more poems to write. The poem’s activities are ongoing, and it has kept going so long as it is interesting to me. There is no narrative, no plot outline, and in terms of seriality (building a forensic argument inferentially, by leaps and movement)—the poem works only in the most general way. It is not about a personal story, or an expressivist narrative of realizations. It’s a series of explorations into the world and into it. The scale change from the little dot of “I” to the magnitude of “it” is what interests me. Sheer amazement and political mourning are two of the most salient aspects of the work.

Now imagine a rectangle divided into units, 19 units on one side, 6 on the other. The grid of 114 spaces offers a map of the written and the few still unwritten poems of Drafts. Imagine specific threads linking the sections, going in all possible directions, both spatially and even temporally—this is a field of practice much looser and less numerological. These threads are thematic recurrences, the line and phrase repetition, the echoes and recalling of words and cadences across the sculptural and spatial distances of Drafts. Between Draft 19 and Draft 20, quite early in the project, it occurred to me that I did not have to go endlessly one to one to one, but could “begin again”—certainly a Steinian move. That is, in its early phase (1986-1993), Drafts seemed to declare a palette of themes and allusions. To build a working matrix for these poems, I decided both to repeat some version of these themes and materials in the same general order every nineteen poems, folding one group over another, making them, in H.D.’s terms “the same—different—the same attributes,/ different, yet the same as before”— (Trilogy II, sec. 39). By beginning again, I could construct a fold or crease or pleat so the particular poems that touch are related. The deep feelings of the fold, the sense of random diagonal links and repetition establishes the possibility that all parts of the work are involved with all other parts, each touches on all. There is a topology of mutuality, even mutual pleasure and relatedness.

That is how the fold, as well as the grid, became a structural and aesthetic principle of repetition constructing relationships among the works. Looking down the grid, the poems make a simple list or series; looking across the grid, one sees pleats of similarities across “lines.” For example, all the poems in the nineteenth position concern work, and have indicative titles: “Working Conditions,” “Georgics and Shadow,” “Workplace: Nekuia,” “Work-Table with Scale Models,” and “Erg.” Each considers what poetic work is, how it gets done, what its tasks and functions are. The poems on the third “line” often talk of “of-ness” —what we are “of,” community, connectedness (and its failures and losses), the world of things and the unevenness of distribution, political failures and hopes. There are many patterns of repetition, variation, extension, and reconsideration that make up the intense, sometimes sublime, sometimes lyric, sometimes suspicious texture of the work, with its evocative situations—personal, political, existential.

I have “an edgy attraction to history’s material residues”—this said by Walter Benjamin in his essay “Edward Fuchs: The Collector as Historian.” I value the long poem, because its scope, its scale, its flexibility, and its ability to use a variety of genres all open the way to poetic/ poethical and cultural commentary. (The word “poethical” is a suggestive and helpful term from Joan Retallack.) Book-length works and trans-book works, life-poems or endless poems tend to create the power of their own worlds by sheer extent, generating a considerable space for working out assumptions about social and cultural values. Accumulation, pensive commentary, ethical commitments, decided poetic attentiveness, textual exactness and social pilgrimage are some of the advantages of Drafts for their author.

My use of Drafts as an overarching title for this project suggests that all the poems, as well as the whole structure, are only drafts of something beyond themselves, something that is palpable but unattainable. The work is compelled by the illusion that the individual poems aspire to one mysterious and unreachable poem, or some multiplex structure in another dimension, that all the individual poems are versions of something that can never really be completed, never fully be found, never totally be articulated. This feeling of the unknowable and the unreachable is very satisfying to me, for it expresses the messianic deferral characterizing the intellectual and ethical conditions of my calling as a poet.

No comments:

Post a Comment