Voices from the Debris Fields”:A Conversation with Carolyn Forché

This three-part interview with Carolyn Forché took place over the course of the past year and a half and was recorded at three different locations: Carolyn’s house in Bethesda, Maryland; in the bistro of the Washington Square Hotel in New York City; and in her office at Georgetown University. (With regard to the addendum that appears at the end of the interview, I emailed Carolyn following the recent election to ask her if she would like to comment on the results. She responded the next day with a timely paragraph.) I had originally hoped that Carolyn and I could complete this interview in one sitting, but we agreed at the conclusion of our first conversation that we needed more time than a single afternoon to do justice to the arc of both her poetry and her career. Consequently, our subsequent interview sessions focused with greater probity on the “main things” of Carolyn’s multifaceted vocation and avocation as a poet, witness, and scholar. Although we didn’t conclude with any sense of final closure, I felt our conversations reached increasingly higher levels of clarity in their exploration of the ideas, poems, essays, books, vicissitudes, failures, and hard-won successes that have distinguished Carolyn’s eminent career.

Part 3: “Voices from the Debris Fields”

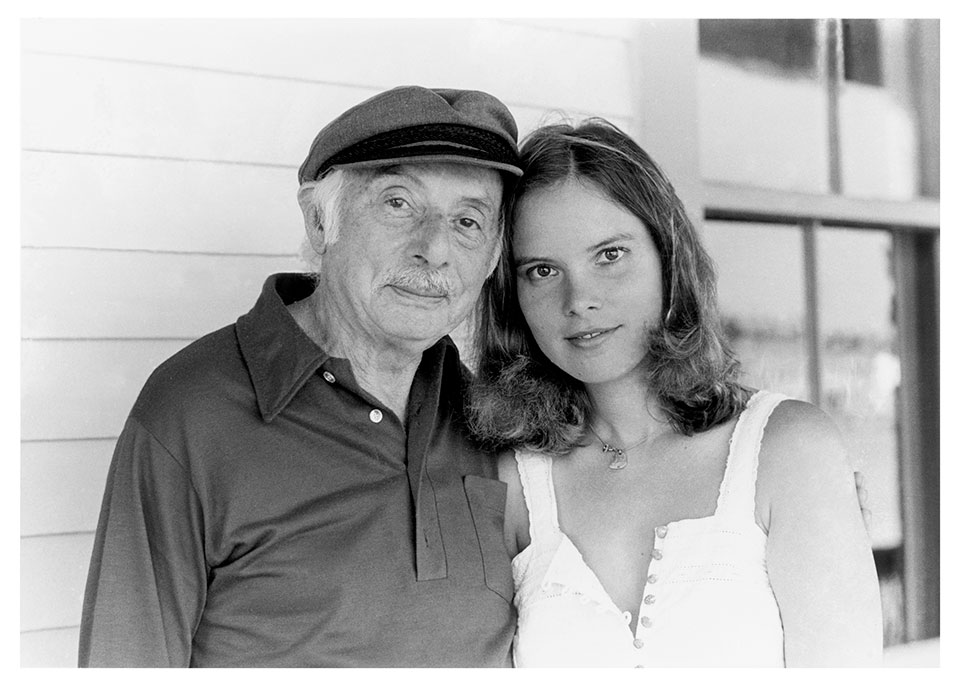

Chard deNiord: I’m curious about what Stanley Kunitz might have said to you about your turn away from the lyrical narrative.

Carolyn Forché: You mean after Gathering the Tribes?

deNiord: Yes.

Forché: Because of Stanley’s historical experience and his wariness of ideological, doctrinaire leftist politics and what happened in the thirties: the Hitler/Stalin pact and Stalin’s imposition of a command economy, collectivization, and the Gulag, he was justifiably skeptical and wary. He did not perceive a path that didn’t run straight through that doctrinaire leftism. He liked The Country Between Us, but he also said, “But that’s enough of that now.”

deNiord: He respected your move away from your early first-person aesthetic of lyricized experience and a subjective first-person speaker to a newfound ambition of witnessing disinterestedly to the atrocities in El Salvador? What did he say to you about this?

Forché: He said something like, “You know you cannot be an activist and stay engaged overseas. This is not the life of a poet. And your work must make a turn away from this because it’s a trap, it will destroy you, and it will destroy your work.” I think he was worried that I would become subject-driven and message-driven and that my engagement in human rights and social justice issues would overtake my freedom as an artist. I think he thought that. And that’s certainly fair enough. I understood what he was trying to tell me. I just didn’t follow the advice, partly because I knew at the time that I was still writing as I always had, without preconceptions, without, as Keats would have it, “designs upon the reader.” But Stanley was patient and kind toward me always.

Curfew

The curfew was as long as anyone could remember

Certainty’s tent was pulled from its little stakes

It was better not to speak any language

There was a man cloaked in doves, there was chandelier music

The city, translucent, shattered but did not disappear

At the hour between the no longer and the still to come

The child asked if the bones in the wall

Belonged to the lights in the tunnel

Yes, I said, and the stars nailed shut his heaven

|

No comments:

Post a Comment